Let the Dice Fly High

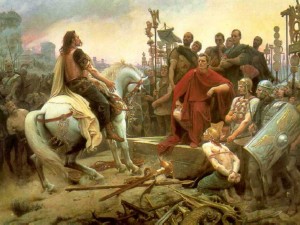

Vercingetorix throws down his arms at the feet of Julius Caesar. Painting by Lionel Royer, 1899.

Caeasar’s successes in Gaul shifted the balance of power he shared with his rival Pompey and prompted his crossing of the Rubicon.

One of the most definitive kairos moments in history unfolded in a cold and dark hour one early January morning in 49 B.C.

Warriors of Rome’s Thirteenth Twin Legion, veterans of the violent Gallic wars that had consumed much of the Roman Republic’s martial energy over the previous decade, stood on the bank of the Rubicon river on the edge of their homeland.

Their loyalty rested on the man who had first led them out of those fields on the opposite side of the river and across the high Alps at their backs. He stood among them, singled out by both the station he had achieved in life and the burden of the decision he was weighing in his mind.

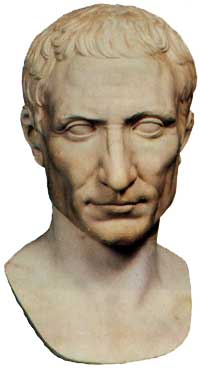

His name was Gaius Julius Caesar, one of two surviving triumvirs of Rome, and he was now the declared enemy of a republic that had dominated much of the Mediterranean world for nearly half of a millennium. His dark eyes peered out from his broad face with the intense stare of a hawk and reflected the flickering light thrown from a nearby torch as he surveyed the unfolding scene. (1)

Caesar’s “thoughts began to work,” wavering as he weighed the consequences of the action of the hour. According to Plutarch Caesar “revolved with himself, and often changed his opinion one way and the other, without speaking a word. This was when his purposes fluctuated most…computing how many calamities his passing that river would bring upon mankind, and what a relation of it would be transmitted to posterity.” (2)

He quietly discussed the situation with a few close advisors. There was little they could say—to the north lay exile and defeat; to the south lay civil war and ruin. Caesar’s next step would be irrevocable, carrying the ripple of drama to the farthest corners of his world.

The lynchpin moment, though great, was short. Caesar had turned fifty years old the previous July, but his decisiveness, energy, and drive were still terrifying traits to behold. Lifting his voice above the din in the darkness behind him, “in a sort of passion,” he abandoned “himself to what might come, and using the proverb frequently in their mouths who enter upon dangerous and bold attempts” Alea iacta est—Let the dice fly high “with these words he took the river.” (3)

Caesar would go on to defeat his enemies as they fled Rome, shaken loose by the speed of his approach and the confidence of the battle-scarred men at his side. He would later crush his rival Pompey in a final battle at Pharsalus in central Greece, despite being outnumbered three to one, and chase Pompey to his death on the far shores of Egypt.

The day would come when he would crown himself dictator of a new Roman empire, launching a new halcyon age for a 500-year-old civilization that would endure 500 years more.

The muddy channel of the Rubicon eventually became lost to history as time eroded the coastal plain it traversed on its fall from the Apennine Mountains running the spine of the Italian peninsula to the west. But the river’s more enduring imprint fossilized into the eponymous symbol of definitive action, the climax in every drama triggering a final denouement away from the familiar.

“Crossing the Rubicon” became the calculated point in a chain of action beyond which one could only press on to a new and different horizon.

What are you prepared to risk when you find yourself standing at your own Rubicon?

(1) “Caesar is said to have been tall, fair, and well-built, with a rather broad face and keen, dark-brown eyes.” Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus, The Twelve Caesars, 1:45, as translated by Robert Graves (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1957) revised by James B. Rives, 2007.

(2) A. H. Clough, tr., Plutarch’s Lives of Illustrious Men (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1881), 517.

(3) Ibid.