Ike the Loser

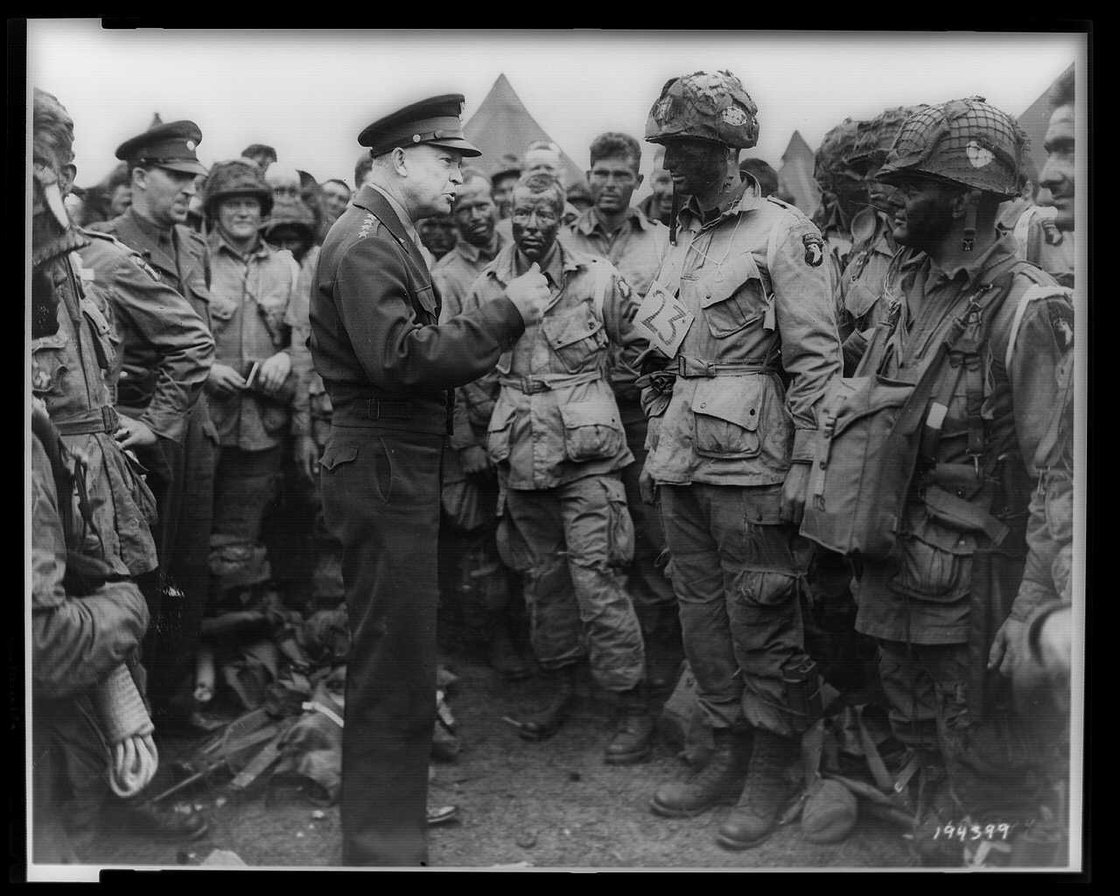

Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower addresses American paratroopers in England on the evening of June 5, 1944, as they prepare for the D-Day invasion. (Library of Congress)

Not all kairos decisions are made on a small stage.

On June 4, 1944, Dwight D. Eisenhower, as the Supreme Commander of all Allied expeditionary forces preparing to invade German-occupied Normandy during Operation Overlord, brooded in his rain-beaten Army trailer knowing he alone was in charge of the largest invasion in world history. At this moment he commanded over 3 million men—over half of them American. (1)

The surprise invasion, two years in the making, consisted of over 10,000 aircraft, 7,000 sea vessels, a night-time airborne assault of nearly 24,000 troops, and a seemingly infinite amount of supporting resources. (2)

No one felt the pressure more than Eisenhower. A reporter who interviewed “Ike”—a nickname stemming from his boyhood days in Abilene, Kansas—that day observed he was “bowed down with worry…as though each of the four stars on either shoulder weighed a ton.” (3)

Every ashtray in his trailer was “full to overflowing” (4) as Eisenhower bolstered his strength with cigarettes from one of the six packs he smoked a day (5), each paired with a constant stream of black coffee.

The next day, Ike walked around the air fields to visit with the paratroopers as they steeled themselves for the battle ahead.

Wandering alone among them, and helpless to do anything more, he asked their names and joked about their jobs, their favorite sports, their wives and girlfriends.

He queried one private, wanting to know if the man was scared.

“No, sir!” came the emphatic reply.

“Well, I am!” Eisenhower said with a sly grin, soliciting cheers from the men huddled around him. (6)

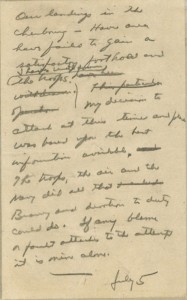

In his pocket, tucked in the folds of his wallet, was a scrap of paper he would never use—a speech scratched out earlier that afternoon in his modest trailer to deliver to the world in case his decision was the wrong one:

Our landings in the Cherbourg-Havre area have failed to gain a satisfactory foothold and I have withdrawn the troops. My decision to attack at this time and place was based upon the best information available. The troops, the air and the Navy did all that bravery and devotion to duty could do. If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt it is mine alone. (7)

He had underscored the last two words—mine alone.

As a good leader, Ike had planned for every contingency, but, as a great leader, he had quietly prepared to become the biggest loser in history. He would take full responsibility for whatever lay ahead.

Fortunately for him—and for the history of the world—kairos luck would shine on Ike’s leadership qualities the next day, June 6, and the successful D-Day invasion would become a turning point in the war against Hitler.

Eight years later, the American public would like Ike, and his great character trait of responsibility, enough to make him the 34th President of the United States.

(1) Michael Korda, Ike: An American Hero (New York, New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2007), 42.

(2) Ibid, 36.

(3) John C. McManus, The Americans at D-Day: The American Experience at the Normandy Invasion, (New York: Tom Doherty Associates, LLC, 2004), 116.

(4) Kay Summersby, Past Forgetting: My Love Affair with Dwight David Eisenhower (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1975), 188.

(5) Merle Miller, Ike the Soldier: As They Knew Him (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1987), 603.

(6) McManus, The Americans at D-Day, 130.

(7) Harry C. Butcher diary, June 8, 1944, Dwight D. Eisenhower Library, Abilene, Kansas.