The Mainspring of Exertion

The sport of beursault developed in the Middle Ages to train military archers in the use of the longbow. Detail from the Luttrell Psalter, circa 1320-1340, in the British Library.

There are beautifully landscaped gardens scattered throughout the countryside of northern France and Belgium dedicated to the local archery sport of beursault.

Developed in the Middle Ages to train military archers using longbows, beursault requires an archer to shoot well in various situations made difficult with changing wind and lighting conditions.

An archer strolling on the path encircling a traditional beursault garden will suddenly come upon a narrow open corridor cut between rows of trees or well-manicured shrubs set in flower beds. Rows of timber or masonry wall panels, varying in height, and interlaced among the greenery on either side, usually shield this corridor from other areas of the garden.

By regulation, the open space between the panel blinds is only five and a half feet across.

Down this open range the archer will spy a round black and white target—known as a butt—placed at the far end of the corridor, a little over fifty yards away, and paired with a similar butt at his feet.

In modern beursault competition, to score a maximum number of points, the archer must shoot a single arrow down this leafy gauntlet and center it in a zone less than two inches wide on the opposite butt.

It takes tremendous skill to shoot an arrow down the cramped space, especially if overhanging branches or other obstructions create a tunnel that constricts the arrow’s natural flight arc.

A special moment occurs when the beursault archer successfully sinks an arrow into the center of the butt at the far end of the corridor.

Many things must act together in perfect synchronicity to achieve this success: a proactive mind, a sharp eye, keen senses in tune with the environment, and the disciplined focus of an athlete controlling a skillful release technique developed from hours of practice.

And, perhaps, a little luck to hold it all together.

As such, at the instant of release, the beursault archer is a physical metaphor of a larger concept the ancient Greeks called kairos, the critical moment in time where opportunity intersects with fortune, or, more colloquially, “the right place at the right time.”

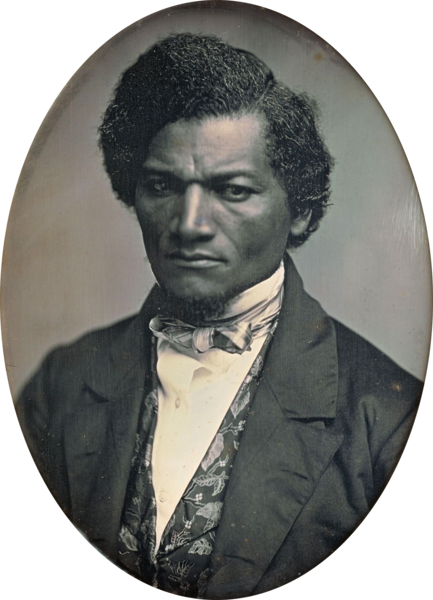

Frederick Douglass, in a famous speech titled “Self-Made Men” that he first delivered in 1859 just prior to the Civil War, also used the allegory of an arrow to analyze the trajectory of a human life in matters of luck, success and fortune. “The scene presented from this view is as a thousand arrows shot from the same point and aimed at the same object,” he said. “United in aim, they are divided in flight. Some fly too high, others too low. Some go to the right, others to the left. Some fly too far and others, not far enough, and only a few hit the mark. Such is life. United in the quiver, they are divided in the air. Matched when dormant, they are unmatched in action.”

But Douglass—a former slave who by then had, through hard work, determination, and the sheer power of his pen, risen to become one of the most famous and eloquent opponents of slavery in America—rejected the theory that luck alone separated the lives of great men and women from the mass of less successful people around them.

A voracious reader of history who knew many of the great men and women of his own time, Douglass recognized that “it is one of the easiest and commonest things in the world for a successful man to be followed in his career through life and to have constantly pointed out this or that particular stroke of good fortune which fixed his destiny and made him successful.”

With keen intellect, he scrutinized and criticized those who made apologies for their own lack of effort. “If not ourselves great, we like to explain why others are so,” he said. “We are stingy in our praise to merit, but generous in our praise to chance. Besides, a man feels himself measurably great when he can point out the precise moment and circumstance which made his neighbor great.”

His “main objection to this very comfortable theory is that, like most other theories, it is made to explain too much. While it ascribes success to chance and friendly circumstances, it is apt to take no cognizance of the very different uses to which different men put their circumstances and their chances. Fortune may crowd a man’s life with fortunate circumstances and happy opportunities, but they will, as we all know, avail him nothing unless he makes a wise and vigorous use of them.”

Opportunity was important but exertion was “indispensable” to the son of an illiterate slave who had worked hard at every opportunity to educate himself as a young man, often at the risk of his own life.

Douglass, from hard-won experience, knew well the stubborn fact that the process of learning from the past of others and then rolling up the sleeves to “Work! Work!! Work!!! Work!!!!” was the key to future personal success, regardless of the trials or tragedies experienced along the way.

A kairos moment would then provide the necessity required for what Douglass called “the mainspring of exertion.”

“The presence of some urgent, pinching, imperious necessity, will often not only sting a man into marvellous exertion, but into a sense of the possession, within himself, of powers and resources which else had slumbered on through a long life, unknown to himself and never suspected by others. A man never knows the strength of his grip till life and limb depend upon it. Something is likely to be done when something must be done.”

If we, like Douglas, make a close study of history, we will realize that the people who lived before us often succeeded in the extraordinary moment of their lives because of how they regularly worked and conducted themselves in their ordinary moments.

They were once skilled archers in the beursault garden of history who found success in the right place and the right time.

This knowledge can inspire us to emulate their most valuable aspects—courage and determination, character and integrity, knowledge and enthusiasm, loyalty and sacrifice, self-dependence and a proper work ethic—and adopt them into our own daily life.

These are simple virtues, but virtue can be the hardest thing to come by in a hard moment unless it is regularly practiced into muscle memory. This is the best we can do to prepare for our own kairos moment when it comes—and it will.

In the end, these lessons found in the exploration of kairos moments are the greatest contributions our very human predecessors gave to us—and to history.

For the complete text of “Self-Made Men” visit http://www.monadnock.net/douglass/self-made-men.html