Leader Notes: First Impressions Matter

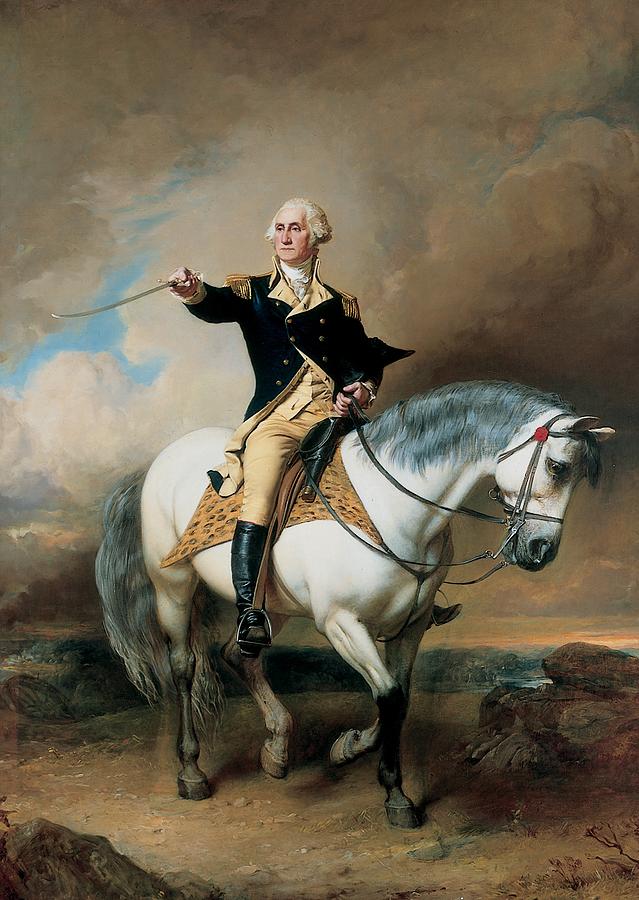

First impressions matter, as they open the door to a greater trust. George Washington knew this and often leveraged his physical appearance to his advantage.

Astride his spirited hunter Blueskin (not as steady under fire as the celebrated “Old Nelson,” a chestnut powerhouse sixteen hands high that he would later receive from his friend Thomas Nelson of Virginia a few years into the war) George Washington cut a magnificent figure riding with his aides on the road to Trenton in the early morning hours after Christmas Day 1776. Washington had long ago learned how helpful a projected image could be toward achieving one’s goals, and had been attentive to his own image ever since his youthful introduction to the wealthy Tidewater planter society. Towering over six foot two inches tall, with intelligent blue eyes set in a broad face above a proud jaw, his pristine appearance in full dress uniform at the Second Continental Congress had certainly helped to seal his commission, at forty three years of age, as commander of the fledgling American army.

Whatever inner turmoil Washington was feeling that early December morning, his men were awed by the calming silhouette of the stoic commander riding beside them in the dim light thrown by torches being kept at the ready to light the cannons. Beside him rode William Lee, Washington’s personal slave and closest assistant, who dazzled the puritan New Englanders with his exotic turban and riding coat. One Connecticut soldier remembered the scene years later. “The torches of our field pieces stuck in the exhalters sparkled and blazed in the storm all night and about day light a halt was made at which time his Excellency and aids came near to the front on the side of the path where soldiers stood. I heard his Excellency as he was coming on speaking to and encouraging the soldiers. The words he spoke as he passed by where I stood and in my hearing were these: ‘Soldiers, keep by your officers. For God’s sake, keep by your officers!’ Spoke in a deep and solemn voice.” (1)

But the wonderful thing about Washington’s leadership style was his authenticity; he truly possessed rare skills that backed up his image of commander-in-chief. Take, for example, his exceptional horsemanship. He had spent most of his adult life in the saddle, riding daily among the farms of his beloved Mount Vernon plantation. He was considered an exceptional rider even by Virginia horse-class standards, riding in an old-fashioned style. Thomas Jefferson praised him as being “the best horseman of his age, and the most graceful figure that can be seen on horseback.” (2)

But it was while “passing a slanting, slippery bank” that Washington’s great physical strength and horsemanship were on full display. Blueskin lost his footing in the darkness and the great horse’s hind legs began to slide out from under him. Instinctually, Washington rose up in the saddle and “seized his horse’s mane,” shifting his weight and literally pulling the animal back onto its feet. (3) Such skill awed men who lived in an age when everything moved by horsepower alone.

Much of the time, Washington’s sheer physicality was enough to inspire initial loyalty and allowed him to build upon men’s first impressions of him through his honest conduct. Benjamin Rush regarded Washington as having “so much martial dignity in his deportment that you would distinguish him to be a general and a soldier from among ten thousand people.” (4) After seeing Washington’s calm presence in uniform at the Second Continental Congress, John Adams, never one to suffer fools, remembered that “I had but one gentleman in my mind for that important command and that was a gentleman from Virginia…whose skill and experience as an officer, whose independent fortune, great talents and excellent universal character, would command the approbation of all America, and unite the exertions of all the colonies better than any other person in the Union.” (5)

Though it seems a simple thing, Washington’s confident, commanding presence inspired his weary men in a very dark hour even if it was, in reality, his first time acting as a field commander in the war.

(1) William S. Powell, “A Connecticut Soldier Under Washington: Elisha Bostwick’s Memoirs of the First Years of the Revolution.” William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd series. 6 (January, 1949), 102.

(2) Thomas Jefferson, quoted in Paul K. Longmore, The Invention of George Washington (Berkley, CA: University of California Press, 1988), p. 182.

(3) Ibid.

(4) “Benjamin Rush to Thomas Rushton, 29 October 1775,” in Letters of Benjamin Rush, Vol. 1, ed. L.H. Butterfield (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1951), 92.

(5) John Adams, as quoted in Harlow Giles Unger, The Unexpected George Washington: His Private Life (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 2006), 102.

Additional reading:

http://www.mountvernon.org/research-collections/digital-encyclopedia/article/nelson/