A Ray of Light

Before there was Steve Jobs and the iPhone there was Johannes Gutenberg, who died today in 1468.

Gutenberg, a German goldsmith and engraver, invented a mass-producing movable type printing press that sparked a revolution in the marketing of communication which laid the foundation for no less than the Renaissance, the Reformation and the Age of Enlightenment.

Daniel J. Boorstin called Gutenberg “a prophet of newer worlds where machines would do the work of scribes, where the printing press would displace the scriptorium, and knowledge would be diffused to countless unseen communities.” (1)

For the first time in European history, ordinary people could enjoy classics by Aristotle, Caesar, or Plutarch, along with simpler works like Aesop’s fables, that could be purchased cheaply in the local marketplace.

Without question, this spread of literacy and learning to the masses permanently, and sometimes violently, changed the social makeup of Europe in a manner similar to how social media is currently revolutionizing certain areas of our own modern world.

Other inventors, chiefly the Chinese, had experimented with printing prior to Gutenberg. So what was it that set him apart and led to his crucial success?

Like Jobs, whose most sparkling inventions occurred after being fired from Apple, Gutenberg displayed a dogged determination to perfect his product to the level of art in the face of crippling trials, all while operating under a shroud of secrecy to keep his competitors at bay.

Gutenberg’s typecasting device, ingeniously simple, took years to perfect and a huge amount of capital, all of it borrowed from impatient investors.

He obsessed in the details, determined to ensure his printed page was precise in its design and brilliant in its color.

Unwilling to rush his unfinished product to market, Gutenberg lost a lawsuit in 1455 that required him to pay a fortune in fees and cost him all of his materials and equipment, including pages from the Bible he had long been working on.

Still determined to succeed, he persuaded a new investor to advance him a full set of printing equipment, and carried on.

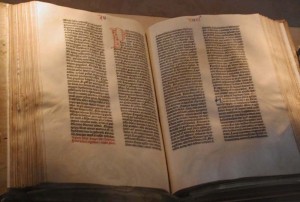

The result of his perseverance can be seen in the Gutenberg Bible, a copy of which is on display in the Library of Congress.

It is truly a work of art. Bibliophiles agree that this first book printed in Europe is still among the most beautiful.

As Boorstin points out, “the technical efficiency of Gutenberg’s work, the clarity of impression and the durability of the product, were not substantially improved until the nineteenth century.” (2)

Legend has it that the idea for the press had earlier come to him “like a ray of light” but it was Gutenberg’s determination that brought that light to a dark age. (3)

It was a kairos moment that changed the world.

(1) Daniel J. Boorstin, The Discoverers: A History of Man’s Search to Know His World and Himself (New York: Random House 1983), 510.

(2) Ibid, 515.

(3) James Burke, The Day the Universe Changed (Boston, Toronto: Little, Brown and Company 1985).